By CRAIG NAKANO, SEP. 20, 2007, TIMES STAFF WRITER

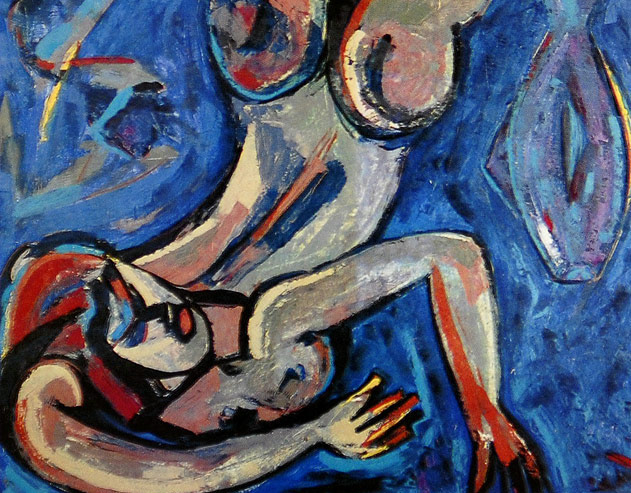

RING the bell, and Laurie Frank soon appears with a gracious smile, delivering the warmest of welcomes before uttering so much as a word: She swings open an arched door dotted with 25 star-shaped windows, and shafts of sunlight sweep across the entry floor like little hands beckoning you inside. By the time you reach the living room, the urge to kick off your shoes takes hold. The rippled teak floor underfoot, the intriguing silhouettes by artist Qingnian Tang that stir the imagination, even the painstakingly selected shade of taupe paint warming the walls -- it’s all so peaceful yet revitalizing, pleasant in the most flattering sense of the word. It’s so pleasant you hate to mention Oct. 27, 2004. But you must.

The fire, you say. How did it start?

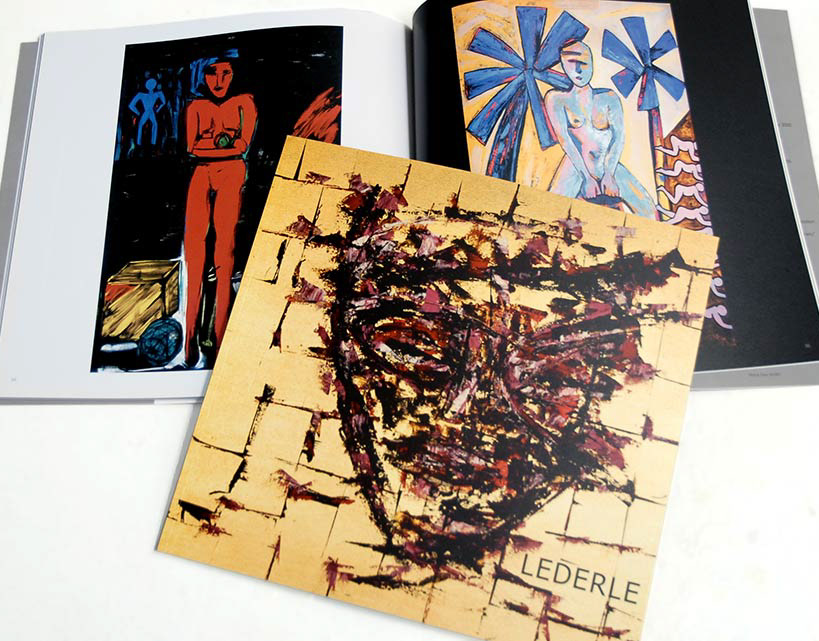

Frank pauses. The smile -- the gentle one that can make strangers feel as though she is a long-lost friend -- ebbs from her face. She rises from her chair, walks to the kitchen with shoulders stiff and returns with a pack of Camels. “By the time I got here, there were seven firetrucks,” she says after one puff, shaking her head. “It was surreal.” Surreal to her, and news to anyone who recalls Home’s previous cover story on Frank. She was profiled in 2003 as a Martha Stewart-meets-Marie Curie party alchemist, throwing together an unlikely mix of friends and strangers for fabulous soirees at her home in the Hollywood Hills. Entertainment-industry connections from her days as a screenwriter mingled with a circle of artists from her new life as owner of Frank Pictures Gallery at Bergamot Station. Neighbors sipped martinis with Frank’s old Yale pals.

Guests remember the parties well.

LOS ANGELES TIMES HOME SECTION 9/20/20017

“Bacchanal orgies, excellent coke,” says “Georgia Rule” and “About Schmidt” producer Michael Besman. “Kidding! No, she just would have this gathering of interesting people -- some you knew, some you didn’t, some you hadn’t seen for ages. It was just a really fun, relaxed atmosphere.”

Slate blogger Mickey Kaus declared at the time, “I realized half the people I knew in Los Angeles I met in this room.”

Back then, the cover photo showed a dinner host’s dream: candlelight and fine food, guests lost in conversation. The 1926 Mediterranean once owned by Maurice Chevalier glowed with good cheer.

Sixteen months later, the home was gone.

--

A passing jogger was the first to notice something amiss and knocked at the neighboring house. Frank Newcomer answered the door.

“I opened it and a woman fairly calmly said, ‘Did you know the house next door has black smoke rising from it?’ ” says Newcomer, who went out in stocking feet to investigate.

An electrical short in a clock had turned Laurie Frank’s kitchen into an orange ball of fire, something Newcomer only half-jokingly compares to the “Backdraft” set at Universal Studios. He summoned neighbor Ed Trillo for help, broke into the house and beat back the flames until the fire crews arrived to finish the job.

Meanwhile, the calls went out: Where’s Laurie? Neighbors phoned friends, friends called party acquaintances, and word spread through Frank’s vast network of dinner companions. The subject of their frantic search, it turns out, was on her way to the now-defunct L.A. restaurant Alto Palato for friend Ana Roth’s birthday party, and not even Frank knew that her cellphone battery was dead.

By the time she arrived at the restaurant, Roth was waiting with the news. The two drove back to Whitley Heights together, arriving to find the flames already subdued.

“It didn’t look that bad from the outside,” Roth says. “But the water damage was the worst. When she went inside, it was devastating.”

Representatives from insurance adjusters and building contractors had already descended on the scene with business cards in hand, Frank says, still shuddering at the thought.

Dozens of friends and neighbors who had heard about the fire converged on Whitley Heights too, lending their support. In some ways it was a classic Laurie Frank get-together, except the party was more like a wake, the poached salmon and caviar potatoes replaced by soot and smoke.

Ever the hostess, Frank fell into her usual routine. “I didn’t know what to do,” she says, “so I just started introducing people to each other.”

--

THE year that followed was no less bizarre. The devastating loss was offset by the relative pleasure that came with moving into a bungalow at the Chateau Marmont, courtesy of her insurance company, while plans for rebuilding took shape.

Frank began collecting replacement furniture and stored it at her art gallery. Visitors began flocking in specifically to see her latest decorating purchases, and some asked to buy her epic sofa designed by Julia Winston Adams or the hand-soldered, hand-painted metal dresser, a “completely bizarre” piece that Frank says is her new favorite.

“I could have sold that maybe 20 times,” she says, still with disbelief.

But for every pleasant surprise, she endured a dozen setbacks. As a resident in a Historic Preservation Overlay Zone, Frank needed all building plans approved by a board that couldn’t get a quorum for six months straight, she says.

Near-record rainfall deluged L.A. that first winter, delivering more than 17 inches of precipitation in one 15-day period. Whatever hadn’t been ruined by smoke or doused by firefighters’ hoses was soaked by Mother Nature. Construction ground to a halt.

The homeless took up residence in the remains of the structure, the savviest of the bunch bringing with them a book on squatters’ rights.

Then came news from the insurance company: It would pay for the Marmont no more.

“She was kind of scared,” Besman says. “She had to move out of the Chateau. She was wondering how long before the insurance money ran out. It was incredibly stressful.”

He took Frank in, letting her use his basement as her home for the next year-plus as construction dragged on.

The house was taken down to the studs. Electrical and plumbing were replaced. The heating still wasn’t operational when Frank decided she had been away long enough.

“It was freezing. I didn’t care,” she says. “I had to get back home.”

Her first day in the newly rebuilt house? The main sewer line -- the only pipe that had not been replaced -- broke and flooded the first floor.

--

WHAT’S most amazing about Frank’s home today is that you’d never know that it -- and she -- have been through so much. Walls, windows and furniture may be new, but the place feels lived-in and familiar -- comforting, like the face of a childhood friend.

“The history of this house means everything to me,” says Frank as Daddy, a 75-pound Louisiana Catahoula leopard dog given to her by painter Ed Moses, inelegantly curls up in her lap. “This house has been my husband. In many ways, it has been my most fulfilling, most difficult and most exciting relationship. Hanging onto it has been the focus of my life.”

With neither husband nor children -- and no earth in her astrological chart, she says -- this house has kept her rooted. Since Frank bought it in 1988, it has been the biggest constant in her life. “I have almost lost this house for so many reasons, so many times,” she says. “It has rescued me, and now I have rescued it.”

In the rebuilt kitchen, Frank’s vintage O’Keefe & Merritt stove has been re-enameled to its original fire-engine red, and a 200-year-old carpenter’s table now serves as her island. Artist Greg Jezewski took cedar window frames and doors salvaged from a demolished house in Morocco and crafted them into Frank’s glass-fronted kitchen cabinets and closet doors.

The Moroccan motif is carried outside to the concrete tile on her deck, whose railings echo the star pattern on the front door.

What used to be the dining room is now a sitting area facing a wall of photography taken by the celebrated Horace Bristol from the early 1930s to the mid-'50s. Centered on the wall is a new flat-screen TV that Frank often tunes to an old black-and-white film, a moving homage to the past amid Bristol’s still-lifes.

The living room -- the candlelit salon that looked so enchanting in that 2003 Home story -- proves equally warm and gracious in the daylight.

Soft September sunshine spills from the new dining room, formerly the sunroom, where windows frame that most prized L.A. work of art: a view. The quintessential Hollywood panorama beckons outside, the hillsides of eucalyptus and palms interrupted only by stucco homes that glow like the white seed heads of dandelions across vast green slopes.

Friends struggle to define the overall effect, complaining that no single label quite does justice to the house or the woman who calls it home.

Besman spins through several words -- warm, loving, adventurous, fun -- before finally settling on an apt adjective. “Canny,” he says. “Canny about people, trends, taste.”

Roth counters with her own description: gracious.

“Before I met Laurie, I didn’t like Los Angeles,” says the former New Yorker, who planned to live here for two years and instead has stayed for 14. “She has a knack for bringing people together. She’s just a generous spirit.”

--

RATHER than dwell on what she lost, Frank likes to quote the 16th century Japanese poet Masahide: Barn burned down, now I can see the moon.

Indeed, it takes a certain spirit to see a house fire as a happy accident, but Frank can -- at least now.

The sunroom floor onto which friend Nic Valle painted a glorious mythological scene in 1988 now has a post-fire, distressed quality that Frank adores even more. Ditto the living room’s Laddie John Dill artwork, whose golden finish now carries a sooty patina that not only documents its history but also lends a remarkable beauty.

Upstairs, the entry to her office was changed to a pocket door with a translucent sea-green glass pattern that matches the house’s main entrance downstairs.

Antique wooden doors from India that had a burned finish when Frank first bought them look even better today. “The second fire,” Frank says, “only made them more beautiful.”

Every piece comes with a story. The 6-foot-long antique linen passport from Mongolia to China? Won it in a poker match.

That mounted bighorn sheep? Dear, dear Mario -- still smoky from the fire -- has been with her for two decades.

“I was a screenwriter, and to me these objects are like words, and together they form a conversation,” she says. They speak to who she is, where she has been and why this home means so much. At times, what they say can be difficult to hear. The army uniforms of Frank’s father and the wedding dress of her mother were among the items that were partially burned.

“I had to ask myself: Do I keep them because they have emotional significance? Or do I let them go?” she says. “It was agonizing.”

With no living relatives to take the heirlooms when she’s gone, Frank chose to live in the now. She let the damaged garments go. “Everything we have is only on loan to us anyway,” she says.

That includes her newly rebuilt house -- her husband, which she vows to have and to hold, till death do them part.

“He got a face-lift, but he’s still the same person,” she says. “I lost so much in the fire, and yet -- and yet I have so much. At the end of the day. . . .”

Her voice trails off. The dog, for a rare moment, is resting quietly on the floor. The house is quiet, almost too quiet, but not for long. Guests will be arriving soon enough, to share a fine meal, to raise a glass, and to see an old friend. He was gone a while, but he’s back. And he’s looking better than ever.

AFTER THE FIRE

A three-part series on Southern Californians and their quest to rebuild after disaster strikes.

Today: One woman’s three-year odyssey to transform rubble back into a house with history.

Last week: It’s painful to see a house burn down, but watching a garden go up in flames can hurt just as much. What happens when a cherished landscape is destroyed -- and reborn.

Sept. 6: Artist James Hubbell loses his landmark home but not the will to start over.