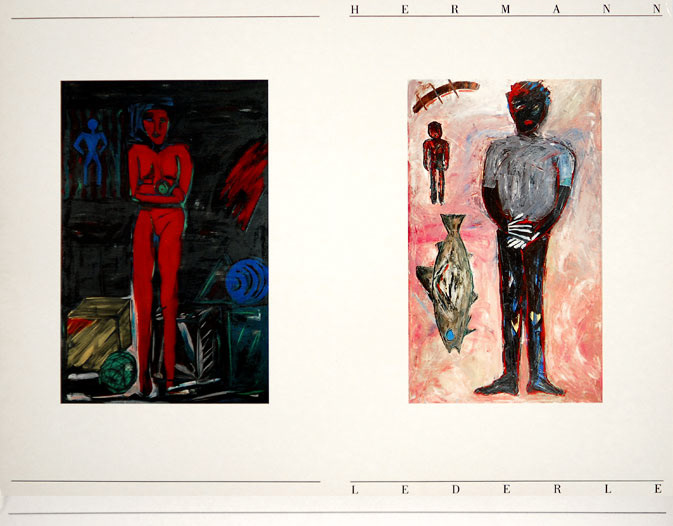

Hermann Lederle’s new work at Lawson Galleries perfectly illustrates Jose Orega y Gasset’s contention in The Modern Theme that art, along with culture, reason and ethics, must enter the service of life. Ortega y Gasset prescribes, among other things, an art that is spontaneous, athletic and imbued with vitality; he finds it most apt that modern public history began on a tennis court in France.

Ortega y Gasset discerns a one-sided tendency in modern European history, the intellectual heritage into which Lederle, a German, was born. Here, there was a separation of culture and life as art distanced itself from the spontaneous life of the person considering it and acquired a consistency of its own: culture thereby became objective, set up in opposition to the subconscious that engendered it (this conceit informs a large part of Michel Foucault’s The Order of Things). Culture, says Ortega Y Gasset, survives only when those who make art and those who view it inject it with a constant flow of vitality. Pictorially this can be illustrated by the difference in conception between the work of Lederle and his contemporaries Julian Schnabel, Francesco Clemente and Mimmo Palladino.